בבוקר, כשאני פותחת את העיניים, אני מרגישה בפעם הראשונה באמת כמו פושעת. כמו האימהות המטורפות האלה שעושות אמבטיה לתינוק שלהן, מלטפות לו את הראש, ואז מחזיקות אותו בתוך המים עד שנגמרות הבועות.

קמה. צועדת לחדר של הבנות. מנערת אותן. ממהרת למטבח. מפשירה ארבע פרוסות לחם. מוציאה מרגרינה מהמקרר. מורחת. מרתיחה. טובלת שני תיוני תה. חוזרת לחדר שלהן. מעיפה את השמיכות. מעמידה אותן על הרגליים, עדיין רדומות. מלבישה אותן בחצאיות תואמות. קולעת להן צמות. מוליכה אותן למקלחת. מורחת לשתיהן משחת שיניים. חוזרת למטבח. אורזת שני סנדוויצ'ים עם מרגרינה לבית הספר. הן מגיעות. מתרסקות על הכיסאות. אנחנו שותות תה. אנחנו שותקות. אני תולה עליהן תיקים. נוקשת להן בלחי. שולחת אותן לבית הספר.

חוזרת למטבח. מתיישבת. מחכה. מוודאת.

קמה. לוקחת מזוודה על גלגלים. פותחת את המקפיא. מוציאה שקיות לחם. שמה על השולחן. מוציאה עוד שקיות לחם. שמה על השולחן. חוזרת למקפיא. שולפת אחד. עטוף בעיתון. שמה במזוודה. שולפת שני. עטוף בעיתון. שמה במזוודה. מניחה מעליהם סמרטוטים. מהדקת טוב טוב. סוגרת את הריצ'רץ'. מחזירה את שקיות הלחם למקפיא. יוצאת החוצה. הולכת לפגוש את פרדריק.

במקרה נפגשנו, לפני שבועיים, באמצע הרחוב. חמש שנים לא התראינו. ישבנו בבית קפה. הוא סיפר על עצמו. השנים עשו לו טוב. יש לו עסק פרטי משהו. לא זוכרת. לא הקשבתי. לא עניין אותי. באמצע נשברתי. סיפרתי הכול. בכיתי. זה הוא הציע לקבור אותם בחצר שלו. מה יכולתי לעשות. חמישה ימים הם יושבים שם במקפיא כמו שני ספינקסים קטנים, מחכים שאמא תעשה סוף סוף משהו, שתמציא להם מנוחה נכונה. לא הייתה לי ברירה. הסכמתי.

במעלית אני מרגישה כמו דיילת שמבריחה סמים מעבר לאוקיאנוס בשביל איזה מאפיונר קולומביאני. ידעתי שהמעלית תיתקע. ידעתי שהכול יהיה נורא. ידעתי ששוטרים יחשדו במזוודה, ייגשו אלי ויבקשו ממני לפתוח אותה. שוטר אחד יציץ פנימה, יסיט ביד אחת את הסמרטוטים, יסתכל לי בעיניים בלי להיות מופתע, ויבקש ממני בקול שקט להתלוות אליהם לתחנה.

המעלית לא נתקעה. יצאתי לרחוב. המזוודה לא עניינה אף אחד. שוטרים לא זינקו עלי. הלכתי למטרו.

לפני שבוע, כשלקחתי את החתולים לווטרינר, ישבו אתי בחדר ההמתנה שתי נשים שמנות ששיכלו רגליים וליטפו את החתולים הסיאמיים שלהן שהיו מונחים בהתאמה על ירכיהן. כשהנחתי את הכלובים על הרצפה הן לכסנו אלי את המבט. לא, אני לא כמוכן, אמרתי להן בלב, אני לא קניתי את החתולים שלי גזעיים, עם תעודות רשמיות, בחמשת אלפים פרנק. אני אספתי אותם עוד כשהיו גורים, ממשפחה שרצתה להיפטר מהם, לזרוק אותם לרחוב, לתת להם למות. הנשים השמנות חזרו לדבר ביניהן. לבסוף הגיע תורי. הרמתי את שני הכלובים ונכנסתי. הנחתי אותם על השולחן. דיברתי עם הווטרינר. הוא לא אמר כלום. רק הורה לאסיסטנטית שלו להכין שתי זריקות הרדמה. פתחתי את הכלובים. הקטנטנים רחרחו את דרכם החוצה. חיבקתי אותם. מחצתי אותם. נישקתי אותם. נתתי להם את הליטופים הכי טובים שהיו לי לתת. הווטרינר עמד בצד והמתין. זזתי הצידה. הווטרינר הזריק להם את החומר. צפיתי בהם כשהם הסתממו; צולעים־נמרחים על שולחן האלומיניום, לא מבינים מה קורה. בסוף הם נרדמו. ליטפתי אותם. מקצה האף עד קצה הזנב. העברתי אצבע רכה על הלחי ותחת הסנטר, כמו שהם אוהבים. הווטרינר לקח אותם לחדר אחר כדי להרוג אותם. ישבתי בפינה כמו ילדה שאמרו לה לחכות למנהלת כדי לקבל עונש. הוא חזר. שתקתי. הוא אמר את המחיר. רעדתי. אין לי מספיק, אמרתי. הוא לא הבין. אמרתי: ביררתי, המחיר הוא זה וזה. נכון, הוא אמר, זה המחיר של הפרוצדורה, אנחנו גובים סכום נוסף בשביל הקבורה. זה לא סכום גבוה, גברת. זה בסדר, לא צריך, אמרתי מהר, אני אקח אותם. הוא לא הבין. התעקשתי: אני אקח אותם. מהכיס הוצאתי את החסכונות האחרונים שלי ושמתי על השולחן. הוא אמר, אין לך כרטיס אשראי? אמרתי: לא. הוא אמר, יש לך איפה לקבור אותם? שיקרתי: כן.

יצאתי החוצה עם שתי הגוויות של החתולים בתוך הכלובים. לא הסתכלתי על שתי הנשים שעדיין המתינו עם החתולים הסיאמיים שלהן. תסתמו, שתקתי, בכלל איזו זכות יש לכן; יושבות פה עם מעילי פרווה ומתנשאות עלי, כאילו שהייתה לי ברירה, כאילו שהייתי מרדימה אותם אם היה לי כסף. הכנסייה נותנת צדקה לבני אדם, שתדעו לכן, לא לחתולים.

הגעתי הביתה. לא ידעתי מה לעשות. עטפתי אותם בעיתון ודחפתי אותם לתוך המקפיא, הכי עמוק שיכולתי. הסתרתי אותם עם שקיות מלאות בלחם. סגרתי. הבנות חזרו אחרי שעה. אמרתי להן שהם ברחו. אמרתי להן שהם מצאו בית אחר לגור בו, בכפר, עם דשא, ועצים לטפס עליהם, ועכברים לרדוף אחריהם, ובנות בדיוק בגילן שמטפלות בהם יפה. כל אחר הצהריים הן צעקו ואני בכיתי. הן צעקו שאני אשמה שלא שמרתי עליהם. אמרתי, נכון. הן צעקו עליי שאני לא יכולה לדעת שטוב להם. אמרתי ששתי הבנות התקשרו מהכפר ואמרו שלחתולים כיף בבית החדש ושהם כל הזמן מתגעגעים אליכן, ומיד ניתקו. הן צעקו עליי שאיך הבנות בכלל יודעות את מספר הטלפון שלנו. אמרתי: בגלל הצ'יפ. הן צעקו עליי שאני שקרנית. אמרתי שאני לא. הן שתקו. מאז הפצע מגליד אצלן ומתפשט אצלי.

במטרו החתולים מתחילים לטפטף. אני כל כך טיפשה. איך לא חשבתי על זה. אני מדמיינת את שתי הגופות הקטנות שלהם נוזלות ומרטיבות את העיתון, נקוות בתחתית המזוודה, ומטפטפות את הטיפות האלה שאני רואה בעיניים שלי נושרות על הרצפה. אחרי ארבע תחנות מצטברות הטיפות לכדי שלולית קטנה מתחת למושב שלי. כולם רואים ושותקים. אני מנסה לכסות את המים האפורים עם המזוודה; מתכננת שכל פעם אזיז אותה קצת כך שהנוזל תמיד יהיה מוסתר. אני מסתדרת עם זה לא רע, אבל את הריח אי אפשר להסתיר. התחנה שלי מגיעה. אני קמה ראשונה. בורחת החוצה. ממהרת להחליף לרכבת הפרברים. חוצה את התחנה ממוקדת ונחושה. המזוודה נגררת מאחורי, מציירת על הרצפות שובל של מיץ חתולים.

ברכבת הפרברים אני עוברת קרון אחר קרון. כולם מלאים. לבסוף אני מוצאת מקום. מתיישבת. מתפללת שרק הנסיעה הזו תעבור בשלום, שאף אחד לא יבוא לשבת לידי, שהכרטיסן לא יגיע. אני דוחקת את המזוודה לפינה, מתחת לשולחן. אבל החתולים ממשיכים לנזול לי מהמזוודה כמו ברז מטפטף. אנשים מתחילים לאתר את מקור הריח. קול שיעול מאחורי. אנשים פותחים חלונות. זוג קם ועובר לקרון אחר. ואני יושבת קפואה. רצינית מאוד. תוקעת את העיניים בחלון כאילו אני היחידה שלא שמה לב מה קורה אצלה מתחת למושב; נוסעת תמימה שמחכה בסבלנות לתחנה שלה. זה הכול בגלל הרצל.

בכל פעם שהוא לקח אותנו לארוחה מפוארת כבר ידעתי מה מצפה לנו. הוא היה מספר על הזדמנות עסקית שפשוט אי אפשר לפספס, נישה שאף אחד לא נגע בה, שוק רעב, פִרצה בחוק, הזדמנות שאם הוא לא ינצל אותה מיד, מישהו אחר כבר יעשה ממנה בוחטות והוא לעולם לא יסלח לעצמו. ואני הייתי מהנהנת כמו מטומטמת, מקשיבה להתלהבות המהפנטת שהפילה כל כך הרבה אנשים בפח. שואלת את עצמי אם זה מה שגרם לי להתאהב בו פעם. הוא התעסק ביבוא של לוחות אלקטרוניים מגרמניה; קרמיקה מסין; עובדים זרים מאפריקה; יום אחד פתח חנות למוצרי קוסמטיקה; אחרי חודש סגר אותה והכריח אותי לתרגם מסמכים במשרדו החדש, שולחן ליד המזכירה שלו, שברור מאילו שיקולים העסיק אותה. במשך תקופה לא קצרה העסקים שלו באמת עלו יפה. הבית שלנו התמלא כל טוב. הוא היה לוקח אותנו להפלגות בספינות פאר, למרות שלא כל כך התלהבנו מהן, סוחב אותנו למסיבות עם השותפים שלו, מתגאה בפניהם איזו אישה יפה יש לו, ואֵילוּ בנות, שעוד כמה שנים בטח יהיו כוסיות.

ואז משהו היה משתבש; העסק התחיל להתדרדר. הוא היה מסתכסך עם השותפים, או שהמשטרה הסתכסכה אתו. היינו צריכות לארוז הכול ולעבור מחוץ לעיר, לפעמים גם מחוץ למדינה. את כל החפצים שקנה בתקופת הגאות, מכר באיזו סמטה לסוחרים שהוא הכיר השד יודע מאיפה. המקרר התרוקן. החובות נערמו. הוא היה נכנס למרה שחורה וימים שלמים שוכב במיטה, מייבב בבכי איום ומאשים את עצמו בקול רם על כמה שהוא אידיוט ואיך יכול להיות שהוא מביא אותנו שוב למצב הזה ולא לומד אף פעם. ואנחנו היינו סולחות לו, מנחמות אותו, מעודדות אותו, כי הוא באמת סבל, והחרטה התעללה בו מבפנים כמו וירוס של כלבת.

אבל הפעם אמרתי לו לא; אני לא לוקחת עכשיו את הבנות ואת כל החפצים שבקושי גמרנו לפרוק מפעם קודמת ועוברת אתו לקמבודיה. גם לא מעניין אותי לשמוע מה הרעיון ואיך נחיה שם כמו מלכות, וכמה טוב שהבנות יכירו תרבות חדשה וילמדו שפה נוספת, וכמה שמחירי השכירות שם מגוחכים, ושבכלל נהיה עשירים שם, ומה אנחנו עושים בכלל באירופה כשהכול פה כל כך יקר.

אתה יכול לנסוע לבד, אמרתי לו, אנחנו נשארות כאן. ולא האמנתי שזו באמת אני שאומרת את הדברים האלה.

למחרת הוא טס. אמר שישלח לשלושתנו, ממש בקרוב, כרטיסי טיסה במחלקת עסקים, עם החתולים, כשרק יסתדר קצת. מאז עברה שנה.

הרכבת עוצרת בתחנה. אני קמה. גוררת את המזוודה. ממהרת לדלת. נתקלת במישהו. לא מסתכלת. יוצאת. מתרחקת בצעדים מהירים. הרכבת ממשיכה בדרכה. רק אז אני עוצרת. נרגעת. נושמת את אוויר הפרברים. הרוח נעימה. שקט מסביב. חמש דקות הליכה מהבית של פרדריק ועכשיו אני כבר ממש בטוחה שהוא לא יהיה שם. שאני אדפוק בדלת והוא לא יענה. כבר מדמיינת את עצמי חופרת בחצר שלו בור עם הידיים, מגרדת את האדמה עם הציפורניים, מכאיבה לעצמי בכוונה. עוברי אורח עוצרים, מסתכלים, מתאספים. ואני עם החתולים. מה קרה להם. שואל מישהו. היא הרגה אותם כי אין לה כסף להאכיל את הבנות שלה. עונה לו מישהי. מי שאין לו כסף להאכיל את הילדים שלו שלא יגדל חתולים. אומר איש גבוה עם משקפי שמש. מי שהורג את החתולים שלו, ככה בלי בעיה, בסוף יהרוג גם את הילדים שלו. אומר צעיר במעיל ג'ינס. זה הכול בגלל בעלה שאין להם כסף. אומרת הבחורה. מי שמאשים אחרים במצב שלו לעולם לא יצא מהבור. אומר האיש במשקפי השמש. אבל למה היא קוברת אותם פה באמצע החצר. שואל הצעיר. כי האקס שלה הבריז לה. זה הבית שלו. הוא הבטיח לעזור לה. אבל עכשיו הוא נעלם. אומרת הבחורה. סומכת על אחרים במקום על עצמה, אומר האיש במשקפי השמש, כל כך אופייני. הייתי צריך לנחש. גם אני במקומו הייתי מבריז לה, שתלמד.

כשהגעתי, פרדריק כבר סיים לחפור את הבור. הוא חיכה לי בפתח הבית והוביל אותי אל החצר האחורית. התכופפתי והנחתי את החתולים בתחתית. פרדריק השתמש באת וכיסה אותם בחול. הוא גם הכין מבעוד מועד שני צלבים קטנים ורשם עליהם את השמות שלהם. עמדנו מחובקים מעל הקבר. הוא הבטיח לי שאוכל לבוא לבקר אותם מתי שרק ארצה. כן, אמרתי, תודה. וידעתי שלא אבוא.

אחר כך נכנסנו אליו הביתה ושתינו יין.

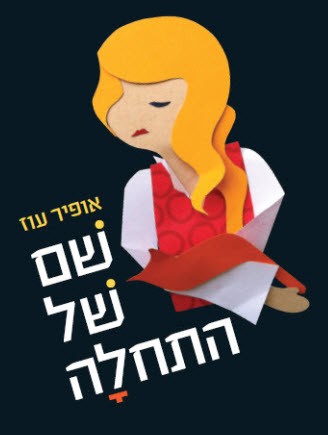

*מתוך ׳שם של התחלה׳.

Criminal

By Ofir Oz

In the morning, when I first open my eyes, is when I really feel like a criminal for the first time. Like the crazy moms who bathe their babies, gently caressing the head, and then holding it under water until all the bubbles are gone.

I get up. Walk to the girls’ room. Shake them awake. Hurry to the kitchen. Defrost four slices of bread. Take the margarine out of the fridge. Spread. Boil. Dunk two tea bags. Walk back to their room. Remove the blankets. Stand them up on their feet, still sleepy. Dress them in matching skirts. Braid their hair. Walk them to the bathroom. Apply toothpaste for them both. Back to the kitchen. Pack two margarine sandwiches for school. They arrive. They crash onto the chairs. We drink tea. We sit silently. I hang their bags on their shoulders. Kiss their cheeks. Send them off to school.

Back to the kitchen. Sit down. Wait. Verify.

Get up. Take the suitcase with wheels. Open the freezer. Take out bagged bread loaves. Set them on the table. Take out more bagged bread loaves. Set them on the table. Back to the freezer. Pull one out. It’s wrapped in newspaper. Put it in the suitcase. Take out another. It’s wrapped in newspaper. Put it in the suitcase. Place rags over them. Fasten tightly. Zip up. Place the bagged bread loaves back in the freezer. Go outside. Go meet Fredrick. 2

We met accidently, two weeks ago, in the middle of the street. We hadn’t seen each other in five years. We sat in a coffee shop. He talked about himself. The years have been kind to him. He owns some kind of business. I can’t remember. I wasn’t listening. I was not interested. I broke down half way through. I told it all. I cried. It was he who suggested to bury them in his yard. What could I do. They have been sitting in the freezer like two little Sphinxes for five days, waiting for mother to finally do something, to find the right resting place for them. I had no choice. I agreed.

Inside the elevator I feel like a stewardess smuggling drugs across the ocean for some Colombian drug lord. I knew the elevator would get stuck. I knew everything would be just awful. I knew the cops would suspect the suitcase, approach me and ask me to open it. One cop would peep inside, move aside the rags, look me in the eye and he would not be surprised, as he quietly asks me to accompany them to the station.

The elevator did not get stuck. I walked out to the street. The suitcase was of interest to no one. Cops did not jump at me. I walked to the Metro.

A week ago, when I took the cats to the vet, two fat women sat in the waiting room with me, their legs crossed, hands caressing their Siamese cats, cradled in their respective laps. When I placed the carriers on the floor they glanced at me sideways. No, I’m not like you, I thought, I did not buy pedigree cats, officially certified, for five thousand Franks. I took them in when they were kittens, from a family anxious to get rid of them, who threw them out into the street and left them 3

to die. The fat women turned back to their conversation. Finally, it was my turn. I picked up the two carriers and walked in. I placed them on the table. Talked to the vet. He said nothing. He only told his assistant to prepare two sleeping injections. I opened the carrier doors. The weeny things sniffed their way out. I hugged them. I squeezed them. I kissed them. I gave them the best caresses I had to give. The vet stood aside and waited. I moved away. The vet gave them the injections. I watched them getting groggy; spread-legged on the aluminum table, clueless about the situation. Finally they fell asleep. I caressed them. From the tip of the nose to the tip of the tail. I passed a soft finger on their cheeks and under their chins, the way they like it. The vet took them to another room to kill them. I sat in the corner like a little girl who has been told to wait for the headmistress to receive punishment. He came back. I was silent. He named the fee. I shivered. I don’t have enough, I said. He didn’t understand. I said: I inquired and was told the price. Right, he said, that’s the cost of the procedure, we charge extra for burial. It’s not a high fee, madam. That’s alright, I added quickly, I’ll take them. He didn’t understand. I insisted: I will take them. I took my last savings out of my pocket and placed them on the table. He said, don’t you have a credit card? No - I said. He said, do you have a place to bury them? Yes - I lied.

I walked outside with two cat corpses inside the carriers. I didn’t look at the two women who were still waiting with their Siamese cats. Shut up, I thought, what right do you have anyway; sitting here with your condescending fur coats, as if I had a choice, as if I would have put them to sleep if I had the money. Just so you know, the church gives charity to people, not to cats.

I returned home. I didn’t know what to do. I wrapped them in newspaper and stuck them as deep as I could in the freezer. I hid them with bagful of bread. Closed 4

the door. The girls returned after an hour. I told them they ran away. I told them they found another home to live in, in the countryside, with grass, and trees to climb, and mice to catch, and girls just their age to treat them nice. They screamed the entire afternoon and I cried. They yelled that I was to blame for not looking after them. True, I said. They yelled at me that I can’t know that they are doing well. I said the two girls from the countryside called and said the cats are happy in their new home and they miss you constantly, and they hung up instantly. They screamed at me that how can the girls even know our phone number. I said: because of the chip. They shouted that I am a liar. I said I am not. They became silent. Since then their wound is healing while mine keeps bleeding.

On the Metro the cats begin to drip. I am such a fool. How did I not think of that. I imagine their two little bodies drip wetting the newspaper, collecting at the bottom of the suitcase, divulging these drops that I see falling to the floor. After four stops the drops form a small puddle under my seat. Everyone sees yet says nothing. I try to cover the grey water with the suitcase; planning to move it a touch every time, to keep the liquid concealed. I manage it quite well, but the smell cannot be hidden. My stop is next. I get up first. I run outside. Hurrying to switch to the suburban train. I cross the station focused and determined. The suitcase is dragging behind me, drawing a trail of cat juice on the floors.

On the suburban train I walk through car after car. They are all full. Finally I find a seat. I sit. I pray only for this to be a peaceful journey, where no one will sit next to me, the conductor will not show up. I cram the suitcase into the corner, under the table. But the cats keep dripping out of my suitcase like a leaking faucet. 5

People start to identify the source of the smell. A cough sounds behind me. People open windows. A couple gets up and moves to another car. And I sit there frozen. Gravely serious. Gazing at the window as if I’m the only one who doesn’t notice what is happening right under her own seat; an innocent traveler patiently waiting for her stop. It’s all Herzl’s fault.

Every time he took us out to a fancy dinner I knew what to expect. He would talk of a business opportunity not to be missed, a niche untouched by human hand, a starving market, a legal loophole, an opportunity he must seize immediately or someone else will make a bundle from it. And I would nod like an idiot as I listened to the hypnotizing excitement that has deceived so many people before. I ask myself if this is what made me fall in love with him back then. He imported electronic boards from Germany; ceramics from China; illegal workers from Africa; one day he opened a cosmetics shop; a month later he closed it, forcing me to translate documents in his new office, separated by a desk from his secretary, who he hired for obvious reasons. For a while there, his business actually picked up nicely. Our house was filled with goodies. He would take us sailing on luxury boats, even though we weren’t enthusiastic, dragging us to parties with his partners, showing off his beautiful wife, and his girls, who will undoubtedly become hotties in a few years.

Then something would go wrong; the business would start to decline. He would quarrel with the partners, or have a brush with the law. We would have to pack everything and move out of town, sometimes even out of the country. Everything he would acquire when times were good, he would then sell in some alleyway to dealers he had somehow known. The fridge became barren. Debts would pile high. He would become all dejected and lie in bed for days, sobbing horribly and 6

blaming himself loudly for being such an idiot and how could he put us in the same position again, never learning. And we would forgive him, appease him, cheer him up, because he really was miserable, and remorse abused him from within like a rabid virus.

But this time I said no. I am not packing the girls now along with all the things we have hardly finished unpacking from the last time to move to Cambodia. I’m not even interested in hearing what the idea is and how we would live there like royalty, and how good it is for the girls to learn about a new culture and another language, and how rent is ridiculously cheap there, and how rich we would be there, and what are we even doing in Europe when everything here is so expensive.

I told him he could go alone, that we plan on staying here. And I couldn’t believe I was really uttering those words.

He flew the next day. Said he will send business class tickets, for the three of us, real soon, with the cats, after he settles in. It’s been a year.

The train stops at the station. I get up. I drag the suitcase. Hurry to the door. Stumble into someone. I don’t look. I leave. Move away hurriedly. The train is on its way. Only then do I stop. Calm down. Breathe in the suburban air. It’s a nice breeze. Surrounded by silence. It’s a five minute walk from Fredrick’s house and now I am certain he will not be there. Certain I will knock on the door and he will not answer. Already imagining myself digging in his yard with my bare hands, scratching the dirt with my nails, purposefully hurting myself. Passersby stop, look, gather. What happened to them. Someone asks. She killed them because she has no money to feed her girls. A woman answers. A person with no money to feed their children 7

should not keep cats. Says the tall man with the sun glasses. A person who kills their cats, just like that, will end up killing their kids too. Says the youth in the jeans jacket. It’s all because of her husband that they don’t have money. Says the woman. A person who blames others for their disposition will never get out of the hole. Says the man with sun glasses. But why is she burying them here in the middle of the yard. The youth asks. Because her ex stood her up. It’s his house. He promised to help her. But now he’s gone. Says the girl. Trusting others rather than herself, says the man in sun glasses, so typical. I should have guessed. If I were in his shoes, I too would have stood her up, serves her right.

When I arrived, Fredrick had already finished digging the hole. He waited for me at his front door and walked me to the back yard. I bent down and placed the cats on the bottom. Fredrick used a shovel to cover them with sand. He also prepared two small crosses and wrote their names on them. We stood there hugging by the grave. He assured me that I can come visit them whenever I wanted to. Yes, I said, thank you. But I knew I wouldn’t come.

We turned and walked into the house.